Who is paying for your electric car?

Exploring the impacts of a corporate-led energy transition

Electric vehicles are seen as crucial for the energy transition. In the global North, as well as in China, they have become the symbol of the envisioned low-carbon economy and already account for more than 10 per cent of new global car sales. Despite their much-vaunted green promises of decarbonising road transport, electric vehicles require extracting a wide range of minerals, such as lithium, graphite, cobalt and bauxite.

Summary

- Electric vehicles are considered crucial for a low-carbon economy.

- However, mining for transition minerals causes massive environmental and social harms in the global South.

- This article looks at the impacts of graphite mining in Mozambique.

As the demand for electric vehicles rises in the global North, large-scale mining operations are expanding rapidly, particularly in the global South. The processes to extract minerals like graphite and cobalt are no different from past mining of coal, copper or gold, with the same harmful social and environmental impacts, including pollution, dispossession of land, loss of livelihoods and cultures, criminalisation and silencing of local activists’ concerns.

This article is part of a series that explores the impacts of the corporate-led energy transition, particularly in the so-called decarbonisation of transport. We start with looking at graphite mining in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique.

False hopes of development

Besides liquefied natural gas (LNG), Mozambique’s province of Cabo Delgado has significant reserves of the energy transition’s “critical minerals” such as graphite, vanadium, and nickel. Out of these critical minerals, graphite has recently taken the spotlight(opens in new window)

due to its use in producing batteries for electric vehicles. The anodes for EV battery packs typically require 50-100 kg of graphite, and it is estimated that the increased global demand of up to 45 million electric vehicles by 2040 will require up to eight times more graphite(opens in new window)

than the amount mined globally in 2022.

Mozambique is among the top five countries for graphite deposits and the second largest producer after China, according to the latest figures from the United States Geological Survey(opens in new window)

. About 10 per cent of the world’s graphite currently comes from Mozambique, which is expected to increase to nearly 15 per cent(opens in new window)

at the end of the decade.

Since the end of the civil war in 1992, Mozambique has experienced significant growth in its GDP while poverty rates have drastically increased, particularly in rural areas. This resulted in greater inequality(opens in new window) . Only a third of the country’s households, for example, have regular access to electricity, which drops to less than 5 per cent in the rural population(opens in new window) . According to World Economic Data, Mozambique ranks fourth in income inequality(opens in new window) . Additionally, the country is ranked among the top ten globally in terms of vulnerability to the effects of climate change(opens in new window) .

The latest country partnership framework with the World Bank states that Mozambique faces the challenge of establishing a climate-resilient economy and implementing policies for low carbon growth. The World Bank identified halting coal extraction and exportation as a top priority for Mozambique’s decarbonisation efforts. The mining capacity of the country, they say, can be used for minerals that are essential for the energy transition and have higher long-term demand and economic value(opens in new window)

.

There are, therefore, high hopes that Mozambique will benefit from the country’s reserves of “critical minerals” such as graphite. This potential is recognised by other interested actors, as seen in a quote(opens in new window)

by US Ambassador Peter H. Vrooman during Mozambique’s Mining and Energy Conference: “These resources present an opportunity to create jobs and drive economic growth, both in Mozambique and the United States.”

However, the multi-layered negative impacts of these large-scale mining operations are often overlooked, and the extent to which countries like Mozambique will benefit from this “green business” is, at the very least, questionable. Justice is at the centre of the question of who bears the burden of the energy transition. The global North’s scramble for critical minerals is reinforcing inequalities and justifying mass extraction of natural resources, often from the lands of already marginalised communities in countries such as Mozambique, to feed the massively disproportionate consumption levels of urban populations in countries like Australia, the US or in the European Union.

Graphite deposits in Mozambique are located in the Niassa and Cabo Delgado provinces, in which colonial and post-colonial history is intertwined with the history of resource extraction. Both provinces have faced ongoing armed conflict since 2017. The conflict has been attributed to radical Islamic insurgency, communities’ marginalisation due to an expanding extraction frontier, and overall lack of economic “development”(opens in new window) . A further expansion of mining in the area risks exacerbating marginalisation, frustration and violent uprisings. This “green business” – extracting critical minerals such as graphite – is, however, of great benefit to the companies, consumers and shareholders in the global North that are eager to jump into and gain from the energy transition.

Foreign, profit-seeking interests prevail

SOMO and the Mozambiquan organisation Tindzila are examining the graphite mining context at Cabo Delgado.

With Mozambique standing to play a pivotal role in the global battery market, Australian mining company Syrah Resources owns a 95 per cent share in a large graphite mine complex in the Balama district in Cabo Delgado. This mining project involves two open-pit mines and is operated by Twigg Exploration and Resources, a subsidiary of Syrah. Syrah Resources is a public company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange and headquartered in Melbourne(opens in new window) . The company grew rapidly from being a low-profile exploration miner with a handful of mineral prospects in the Arab Peninsula and African countries to controlling what the company describes as the world’s largest graphite extractive project outside of China(opens in new window) .

Syrah is not the only multinational corporation extracting graphite from the impoverished and conflict-prone region of Cabo Delgado. Next to Syrah’s operations is the Balama Central Graphite Project(opens in new window)

, a mining concession that Battery Minerals recently sold to the UK-Indian multinational Tirupati Graphite together with another graphite site in Montepuez district, a few dozen kilometres east of Balama.

Additionally, just about 10 kilometres north of Syrah’s mining site, another Australian company called Triton Minerals has a large-scale concession with an estimated 5.7 million tons of graphite(opens in new window)

for at least 25 years. Triton also controls the graphite extraction Grafex project in the Ancuabe district, where insurgent attacks reportedly killed two security guards(opens in new window)

in June 2022.

Next to this is the GK Ancuabe Graphite Mine, a mining company ultimately controlled by the Dutch multinational AMG Advanced Metallurgical Group through a German subsidiary. GK Ancuabe was the first multinational to start producing graphite in north Mozambique(opens in new window)

, and did so with the financial support of a German development bank.

All of these companies and mine operations show the heavy interests at play in controlling the graphite that lies under Mozambique’s soil. It is worth noting that Chinese companies are also investing in the region(opens in new window)

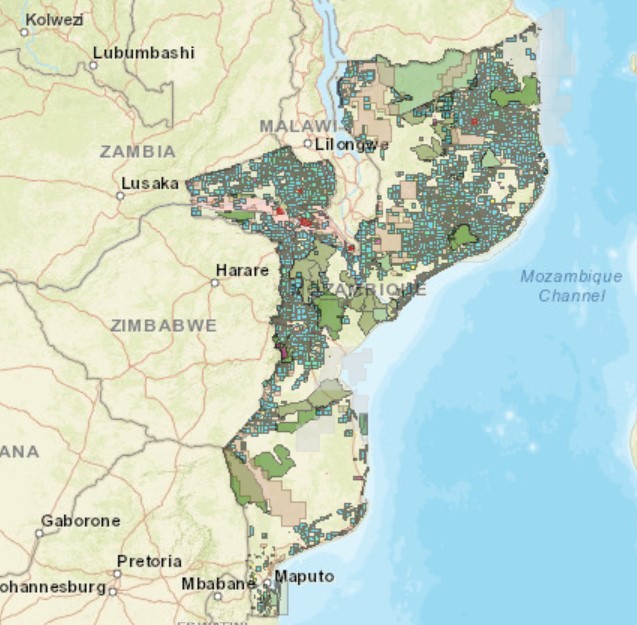

. The map below illustrates the shrinking of land and forests for small-scale farmers and rural families due to mine concessions.

The impacts, especially the cumulative impacts, of these losses are seldom taken as seriously as they should be by the mining industry and its financiers. There is no replacement for lost livelihood options for most communities living around the extraction sites, as the mining industry rarely offers broad employment opportunities for local people.

Likewise, there is no replacement for their cultures, as their lives are tightly intertwined with their lands and forests. The ‘local benefits’ the industry points to are often a reality for only a small number of business people and the few who gain employment.

Feeding the energy transition elsewhere

In addition to its mine concession in Cabo Delgado, Syrah Resources also purchased an anode production facility in Vidalia, Louisiana, US, that positioned the company to be the first and so far only anode producer outside of China(opens in new window) .

To achieve this, Syrah leveraged multiple equity-raising financing options facilitated by Australian, Swiss and US banks, as well as AustralianSuper, one of Australia’s largest superannuation funds and currently the largest shareholder of Syrah. More recently, Syrah secured a $102 million loan and a $220 million grant from the US Department of Energy(opens in new window) , and a $150 million loan from the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC).

The financial support from the US Treasury is tied not only to the Balama extractive project but also to the expansion of the production capacity of Syrah’s anode production facility in the US. Consequently, since 2021, Syrah has entered into agreements with several battery producer companies to supply large volumes of anode materials for electric cars, including Tesla, BlueOval SK, LG Energy Solution and Samsung(opens in new window) .

From the graphite extracted in Cabo Delgado to the electric cars that roll off the Tesla production line, this value chain is driven by the demand for EVs in the global North(opens in new window)

and the energy transition for industrialised countries. The consequences of such a value chain for the communities and families living near the extraction sites are rarely considered when EV sales are predicted to soar.

Syrah Resources claims to be crucial for the energy transition by accelerating the growth of the electric vehicle industry and reducing dependence on China(opens in new window)

. However, Syrah Resources’ prospects heavily depend on the extraction of graphite in Balama, Cabo Delgado. Communities often get the crumbs and bear the harmful impacts of not only the extraction of resources on their territories but also the increasing impacts of the climate crisis. Meanwhile, companies, shareholders and consumers from the global North reap the benefits.

In collaboration with Tindzila, SOMO will closely monitor the situation in Northern Mozambique in the coming months. We will continue engaging with affected communities to better understand the impacts and consequences of the energy transition and raise awareness in the global North, especially with policymakers supporting the increased extraction of minerals in the global South.

While it is necessary to make significant and immediate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions before 2025 to prevent further catastrophic climate disruptions, it is crucial to expose and address the often-hidden impacts of the proposed transport decarbonisation in, amongst others, Europe, North America, and China to avoid reproducing the belief that some communities are expendable for the well-being of the wealthy elsewhere.

Do you need more information?

-

Ilona Hartlief

Researcher

Related news

-

Overconsumption of transition minerals will cost us the earthPosted in category:Opinion

Alejandro GonzálezPublished on:

Alejandro GonzálezPublished on: Alejandro González

Alejandro González -

-