The Netherlands: European champion share buyback

More than USD 157 billion in the past ten years

Taxing share buybacks is on the political agenda in the Netherlands. During the Algemene Politieke Beschouwingen (the parliamentary debate on the new government budget), three parties proposed to scrap the existing tax exemption for share buybacks by listed companies—estimated revenue: € 1.2 billion a year. At least five other parties also want to get rid of this exemption.

The finance ministry’s calculations and the Central Planning Bureau (CPB) arrive at a lower estimate, at around € 800 million a year. Moreover, the ministry wants the exemption, created in 2001, to stay.

In a parliamentary letter dated 26 September, state secretary Marnix van Rij defends maintaining the exemption with two arguments based on input from VNO-NCW, Eumedion and the Association of Stockholders.

First, writes Van Rij, abolishing the exemption would lead to fewer stock exchange listings in the Netherlands. According to him, companies would choose to be listed abroad if cancelled. Second, the state secretary argues that the tax benefit on share buybacks allows companies to easily divest ‘excess profits’ to avoid a takeover.

This article examines these arguments and concludes that the Netherlands is currently the EU leader when it comes to share buybacks and that this excessive buyback has eroded Dutch companies. Since 2001, investments have structurally declined, and debts have increased. This is an unsustainable business model, especially given the need for higher investments in the energy transition.

The tax exemption is also an inappropriate and unjust use of taxpayers’ money; the strongest shoulders should bear the heaviest burden, and loopholes to avoid (dividend) tax should be closed by the government, rather than enabled.

The analysis further shows that the fear of relocation is unfounded when it comes to stock exchange listings. Multinationals with Dutch listings often have few material ties here, their relocation would therefore have no real economic impact.

We use Refinitiv Eikon’s Worldscope database in our research. All the figures mentioned here are from this database.

Fear of companies ‘moving abroad’

According to the parliamentary letter, the dividend tax exemption was introduced in 2001 to “prevent the Dutch treatment of share buybacks from adversely affecting the performance of Dutch listed companies relative to foreign competitors”. Several OECD countries started facilitating share buybacks for tax purposes during this period when more and more companies start doing this in response to a trend that began in the US.

In the public debate on this topic, the argument often comes up that if these profits were taxed unilaterally (read: in the Netherlands), companies would move to another country physically or on paper with their stock exchange listing. But how do Dutch listed companies actually do, compared to companies in countries around us? Note: we work with dollars to facilitate a good comparison with other countries

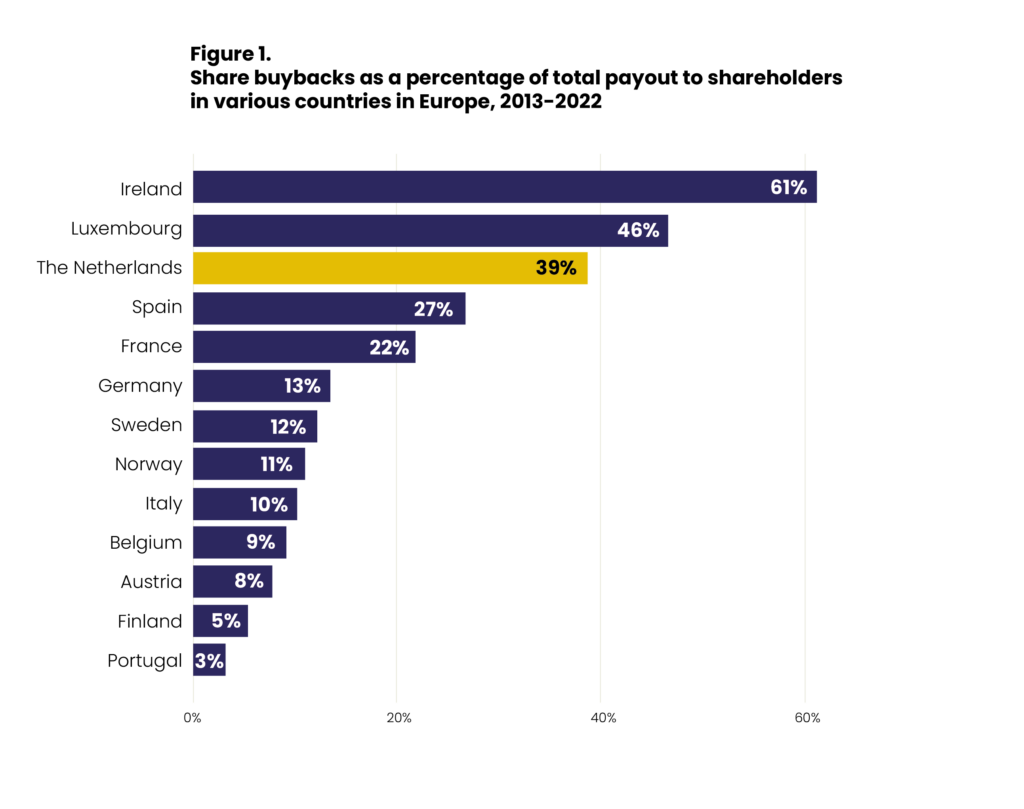

If we look at the figures of share buybacks as a percentage of total profit distribution to shareholders, we see that the Netherlands is in the top tier in Europe (see Figure 1). The Netherlands is among the leaders along with Ireland and Luxembourg.

In the Netherlands, 39 per cent of all profits distributed during this period were paid out through buybacks of its own shares. In Germany, for example, the percentage was 13 per cent. We looked at 7,210 transactions involving share buybacks, in the period from 2013. What is striking is that the EU’s top three tax havens make up the top three in this figure.

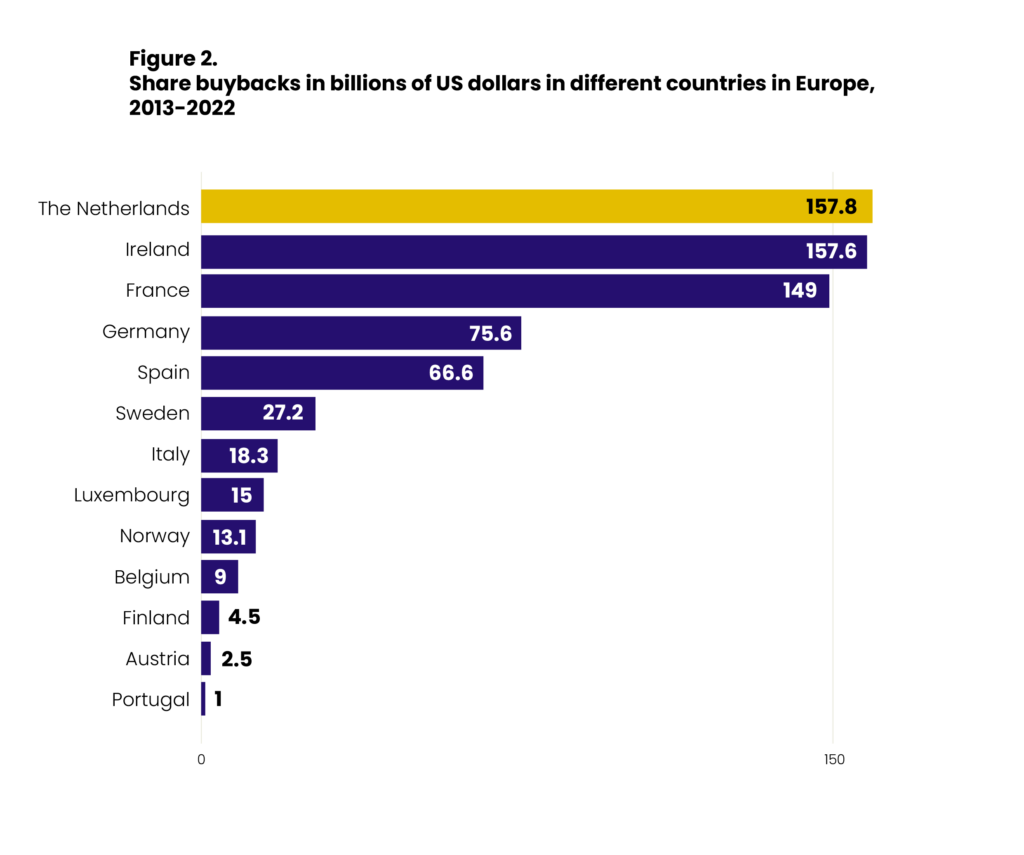

Looking at the total value of all corporate buybacks, the Netherlands tops the list with USD 157.8 billion from 2013 to 2022 (Figure 2). Listed companies in countries such as France and Germany, despite a much larger total market capitalisation, still bought back fewer of their own shares during this period.

This analysis shows that the Netherlands is out of step in the EU regarding share buybacks.

If the Netherlands starts taxing share buybacks again, three things could happen: companies could start paying more dividends, pay out less profits (and invest more), or move their listing to another country.

Currently, a large number of companies are listed in the Netherlands while having little (such as ArcelorMittal) or no (such as Gucci) material connection with the Netherlands (Table 1). These companies are also often subject to taxation in other countries, so a tax on share buybacks does not affect them.

Large internationally operating companies often have multiple stock exchange listings. The relocation of a listing has no material economic consequences; it does not involve the shifting of actual economic activities involving employment.

The parliamentary letter of 26 September states that the tax-free buyback of treasury shares is needed to facilitate companies that make occasional excess profits. If these excess profits are kept on the balance sheet, companies can become easy prey for takeovers, the state secretary argues. Companies prefer not to increase their dividend payout because they would have to reduce it again the following year. Shareholders generally do not like that.

Following this line of argument, it is still unclear why share buybacks should be tax-free. If incidental higher profits are a problem, and if the increase in dividend payments is undesirable, then that is not an argument for leaving share buybacks untaxed.

The underlying problem is that the parliamentary letter describes a non-existent situation. In most cases where shares are repurchased, there are no ‘excess’ profits at all.

For this, we need to zoom in a little deeper into the transactions of companies in the Netherlands and look at the effect on the broader corporate economy. Please note: In this analysis, we only work with Dutch data and as such can use a longer time series than in the comparison with EU countries. Here, we look at the transactions of all companies listed in the Netherlands for the period from 1995 to 2022.

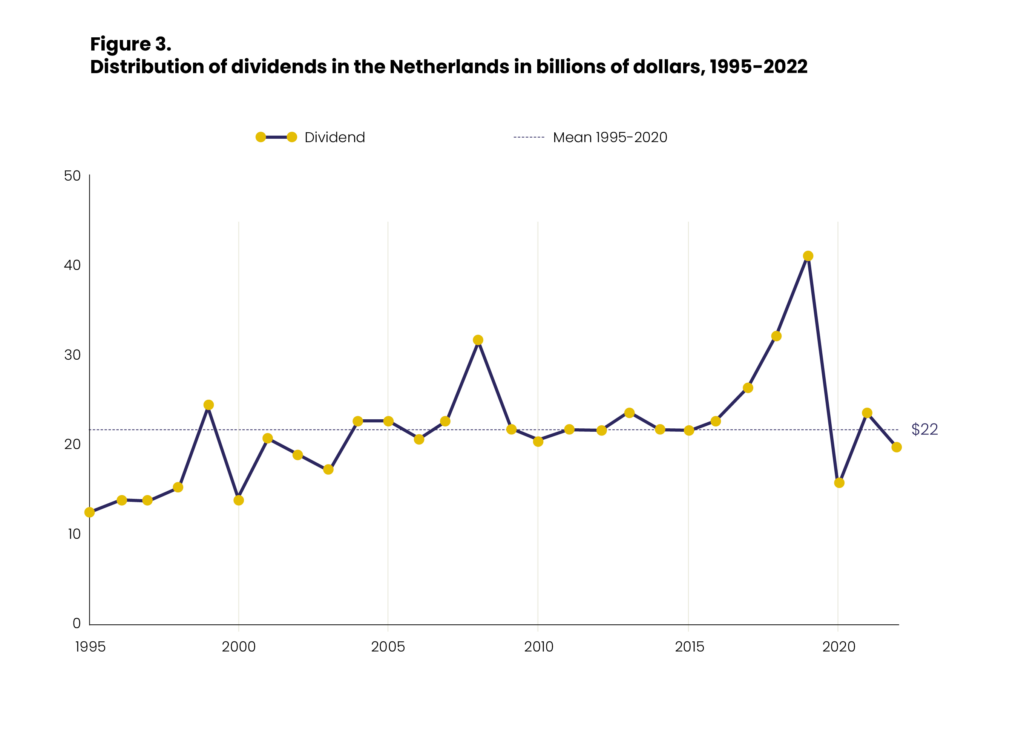

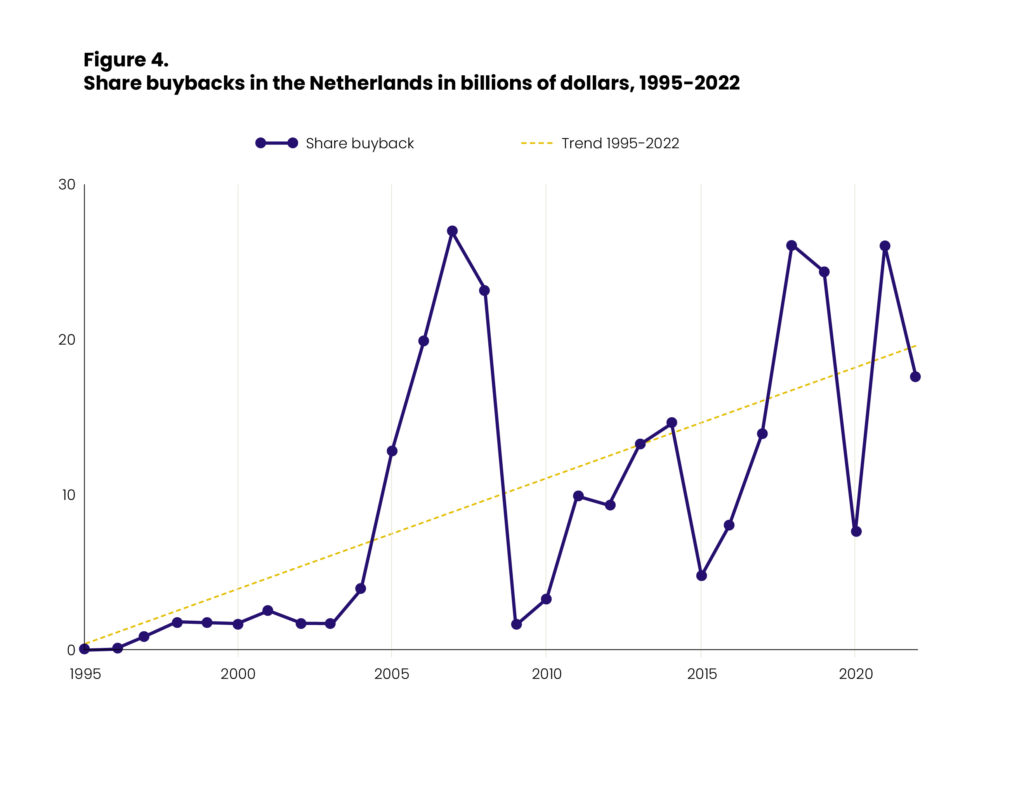

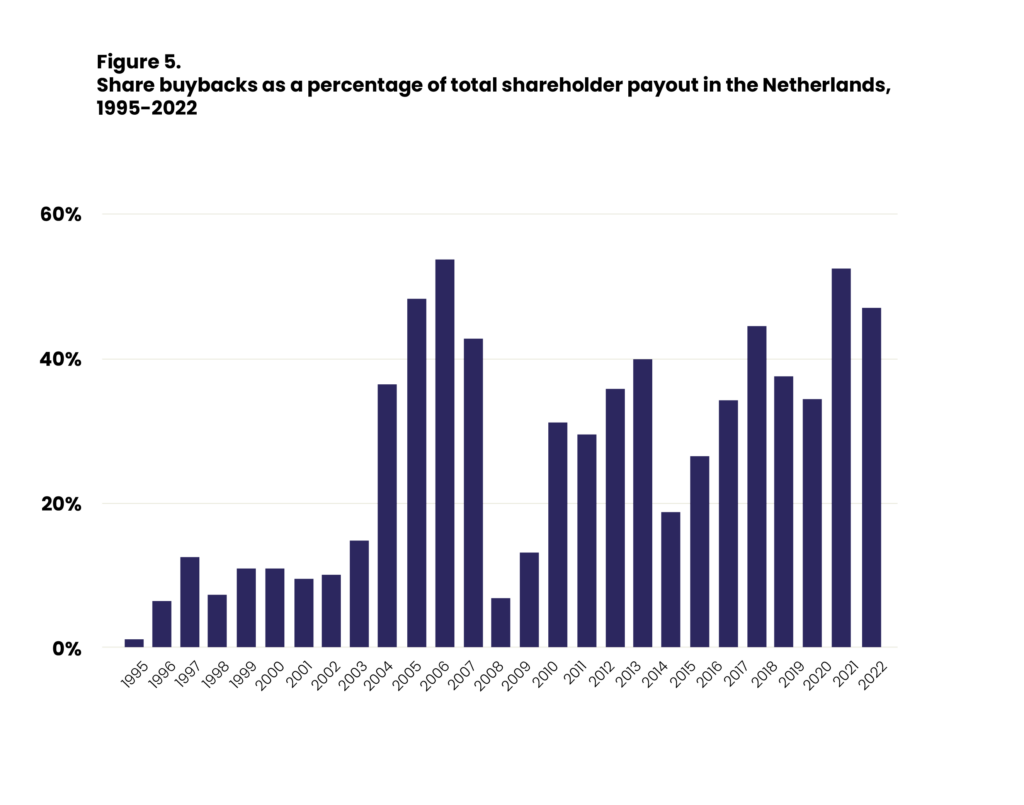

In 1995-2022, USD 282 billion worth of shares were repurchased, and USD 610 billion were paid out in dividends. First, we look at the composition of total distributions to shareholders of Dutch-listed companies. Here, we see the cyclical element of share repurchases: while dividends paid are relatively stable (Figure 3), share repurchases are fairly synchronous with share price movements (Figure 4). As stock prices rise, so do shareholder distributions through share buybacks.

Rich shareholders, hollowed-out companies

Second, we look at total shareholder compensation (share buybacks and dividends) relative to net profit. Here, we see an upward trend in the period 1995-2022. In the period 2000-2005, on average, 56 per cent of net profit is paid out to shareholders. In the period 2015 to 2020, it is 91 per cent. This leaves fewer financial resources to reinvest in the company. Several companies have even paid out more than 100 per cent of net profit for an extended period. In the period after 2015, and for several years in a row, the weighted average of total shareholder remuneration of all Dutch listed companies together exceeded 100 per cent of net profit.

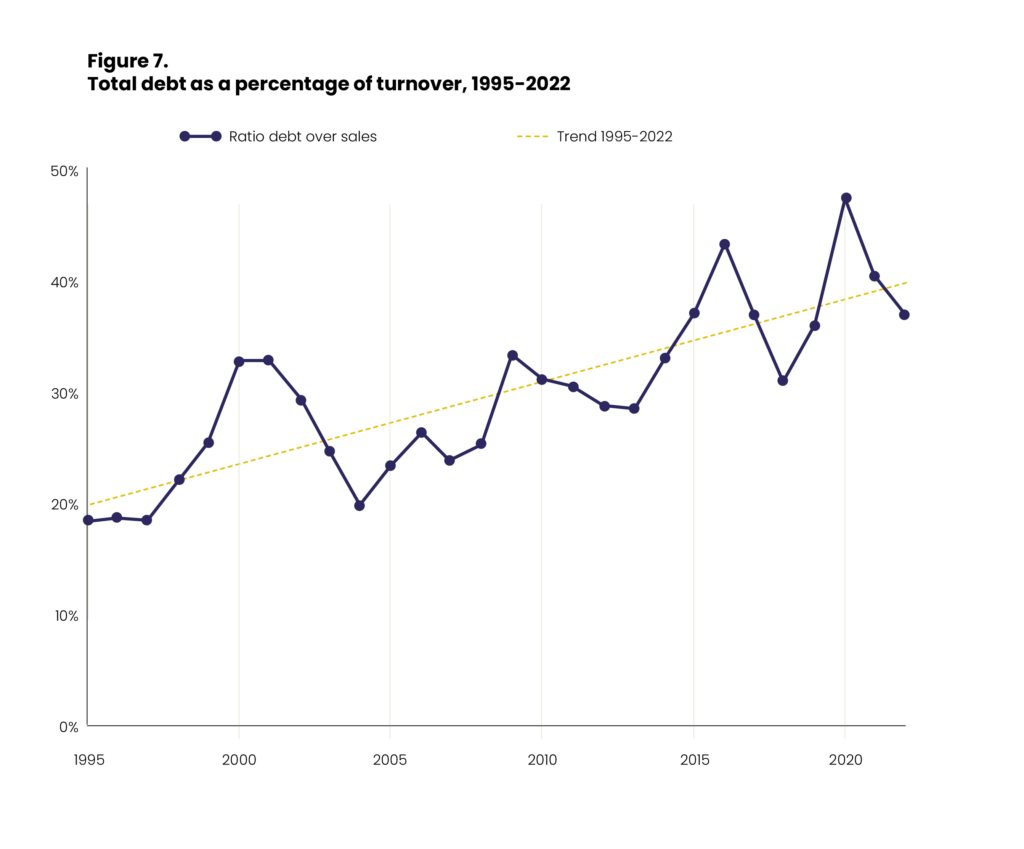

This development can be seen as the ‘hollowing-out’ of companies. As an increasing share of net profit is distributed, less and less remains to reinvest in the company. In addition, we see that the total debt of these companies is increasing. The main criticism that the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has on share buybacks is that it is primarily financed by borrowing. Companies borrow to pay out to shareholders and not to increase or maintain earning capacity to meet debt obligations in the future. Rewarding the shareholder in the short term thus weakens the company in the long term.

The combination of growing debt and share buybacks means that companies have collectively reduced their equity relative to foreign equity (debt). Share buybacks mean a direct reduction in equity. According to the BIS, the combination of both activities over an extended period at companies worldwide means that structural risks have increased, as companies are less able to absorb setbacks due to this behaviour.

Excessive shareholder remuneration at the expense of the climate

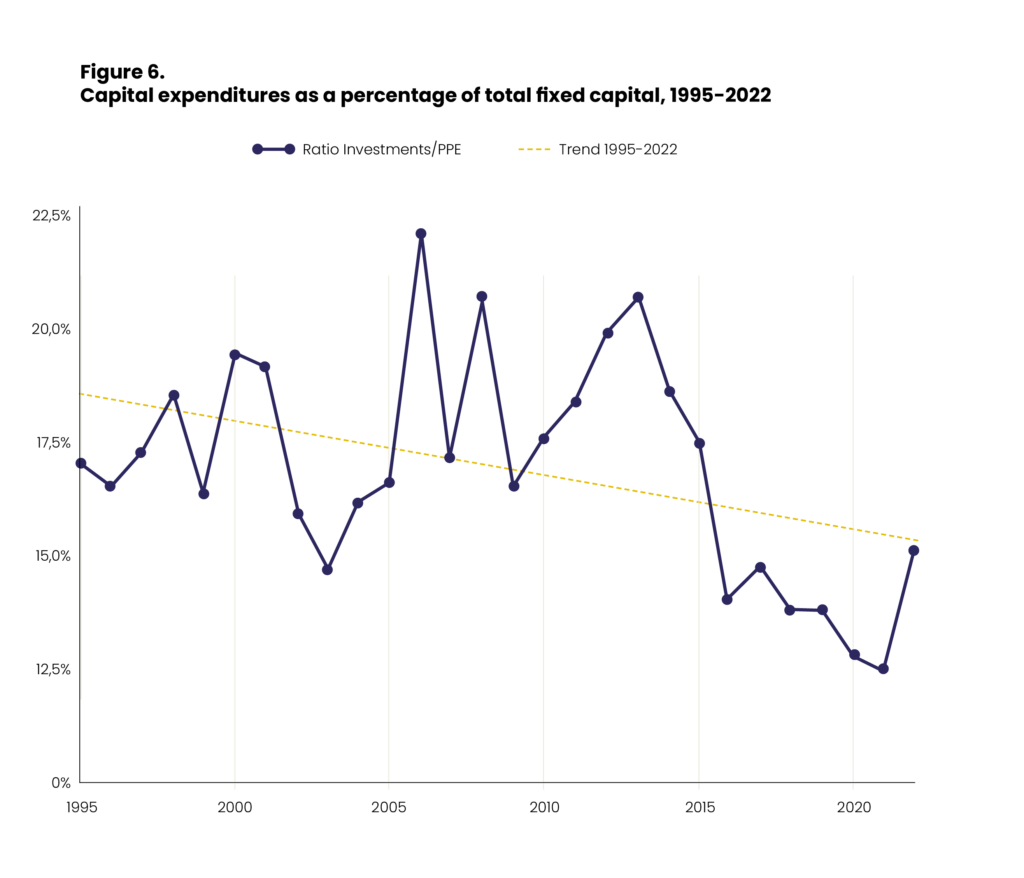

The main problem is that disproportionate shareholder remuneration can only go hand in hand with falling investments (Figure 6) and rising debt (Figure 7). The energy transition requires large investments from companies and room to borrow, while the business model outlined only prioritises short-term shareholder value.

Our analysis contrasts sharply with that of the secretary of state in his parliamentary letter, as it is not the occasional ‘excess’ profits paid out by buying back the company’s own shares. It is a business strategy that erodes companies from within through falling investment and rising debt ratios. The current business model, which focuses on short-term shareholder value, is incompatible with the challenges of the energy transition.

Taxing share buybacks is justified from an equity perspective and essential to promote a more sustainable business model. Moreover, this tax cut costs the treasury a lot of money that could be better spent.

Do you need more information?

-

Rodrigo Fernandez

Senior researcher

Related news

-

Why share buybacks are bad for the planet and peoplePosted in category:Opinion

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on:

Myriam Vander StichelePublished on: Myriam Vander Stichele

Myriam Vander Stichele -

-

Fintech’s red flags Published on:

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication

Myriam Vander StichelePosted in category:Publication Myriam Vander Stichele

Myriam Vander Stichele