Re-cap: UN discussions on the reform of ISDS move on to the next stage

Between 1 and 5 April 2019, members of Working Group III(opens in new window) of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) gathered in New York to continue discussing the possible reform of the investor-to-state dispute settlement (ISDS) system. Some 400 delegates, including 106 states and around 70 observer organisations, participated in the deliberations of the Working Group to decide whether the identified concerns regarding ISDS merit multilateral reform and to commence work on the development of relevant solutions for reform. After a week of intense debates and informal consultations, the Working Group agreed to start working towards developing “structural” reforms, including the EU proposal to establish a multilateral investment court(opens in new window) , while giving states the options to submit other possible solutions.

The UNCITRAL process on ISDS reform

UNCITRAL entrusted one of its working groups with a broad mandate (opens in new window) to work on the possible reform of ISDS in July 2017. Working Group III would proceed to: (1) identify and consider concerns regarding ISDS; (2) consider whether reform was desirable; and, if so, (3) develop relevant solutions. The mandate particularly stressed that “the deliberations, while benefiting from the widest possible breadth of available expertise from all stakeholders, would be Government-led”.

The first two sessions of the Working Group under this mandate took place in Vienna in October-November 2017 and in New York in April 2018, and dealt with the first step of the mandate. During both sessions, delegates from governments and observer organisations raised a wide array of concerns(opens in new window) related to ISDS, with the possibility to raise additional concerns at future sessions. In preparation for the Vienna session in October-November 2018, the UNCITRAL Secretariat prepared a working paper(opens in new window) that listed the main concerns identified by the Working Group. These concerns were categorised by the secretariat into three groups: (1) concerns pertaining to consistency, coherence, predictability and correctness of arbitral decisions by ISDS tribunals; (2) concerns pertaining to arbitrators and decision makers; and (3) concerns pertaining to cost and duration of ISDS cases. A fourth category would cover “other concerns”, that is, additional concerns not identified under the mentioned categories.

The limitations of the UNCITRAL process on ISDS reform

During the Vienna session, several delegates from governments and observer organisations criticised (opens in new window) the narrow scope of the framework for discussions and highlighted that important concerns that had been raised earlier were not reflected in the working paper. While the three categories of concerns relate to issues that are important to address, they do not fully reflect(opens in new window) the broader and structural problems with ISDS that lie at the heart of the current dissatisfaction with the system. These include the asymmetric nature(opens in new window) of the system, the lack of obligations(opens in new window) on foreign investors, the impact on capacities of states to regulate in the public interest(opens in new window) , the relationship with domestic law and domestic courts(opens in new window) , and the impact on third-party rights(opens in new window) and interests. While the Working Group agreed that all of the concerns pertaining to the three mentioned categories merit multilateral reform, it was decided that these “other concerns” were to be addressed during the next session in New York in April 2019 before moving to the third step of the mandate.

What happened in New York?

At the New York session, the Working Group first concluded (opens in new window) that reform was desirable in relation to concerns (opens in new window) regarding third-party funding(opens in new window) (TPF) in ISDS cases. With regard to the “other concerns”, the Working Group discussed a number of aspects related to ISDS that had not yet been addressed in Vienna:

- Means other than arbitration to resolve investment disputes as well as dispute prevention methods;

- Exhaustion of local remedies before bringing claims to investment arbitration;

- Third-party participation in ISDS, including the participation of the general public and local communities affected by the investment or the dispute;

- Obligations of investors, for example, in relation to human rights or the environment as well as to corporate social responsibility, and the possibility of allowing counterclaims by states as well as claims by third parties against investors;

- The regulatory chill effect of ISDS as well as its asymmetric nature, the costs associated with ISDS proceedings and high damage amounts awarded by tribunals, which could undermine states’ ability to regulate; and

- Calculation of damages by arbitral tribunals.

Many of these concerns were raised by countries that have been frequently hit by ISDS claims and that are currently rethinking their bilateral investment treaties, such as South Africa, Ecuador, Bolivia, India and Indonesia(opens in new window) . Nevertheless, the Working Group concluded (opens in new window) that none of these aspects would be addressed as a separate concern, but rather as part of the concerns that had already been identified or as guiding principles for developing reforms under step three of the mandate. Although these concerns are now formally part of the reform agenda, it remains to be seen whether they can be meaningfully addressed within the context of the narrow scope of that agenda.

This content is available after accepting the cookies.

View on Twitter. Opens in a new windowThe #UNCITRAL(opens in new window) Working Group III resumes its work on the reform of #ISDS(opens in new window) . The WG is first to decide whether #ThirdPartyFunding(opens in new window) and 'other concerns' related to ISDS merit multilateral reform, before moving to develop possible solutions pic.twitter.com/M2Xx0y1b0P(opens in new window)

— Bart-Jaap Verbeek (@BJVerbeek) April 1, 2019(opens in new window)

The Working Group then proceeded to discuss a work plan that would guide the further reform process. A number of delegations had submitted their proposals for a work plan, with several governments, including those of Chile, Israel, Japan, Costa Rica and Thailand, calling for prioritisation and sequencing of the most pressing concerns. Others, including the European Commission and the EU member states, called for a more systemic reform, thereby proposing a standing two-tier mechanism (permanent court plus appellate body) as “the only available option that effectively responds to all the concerns identified in the Working Group”. As discussions on these proposals got underway, it soon became clear that it would be very difficult to agree on a way forward.

A proposal by the Swiss delegation was then tabled on Wednesday, which, by way of compromise, suggested a work plan with two workstreams. One workstream could focus on “incremental reforms”, such as a code of conduct for arbitrators, cost issues and counterclaims; another could work towards “systemic reforms”, meaning a permanent court in line with the EU’s proposal. The Swiss proposal was met with considerable support, although many delegations disliked the rigid distinction between “incremental” and “systemic” reform.

A compromise was reached only after extensive informal consultations outside the plenary, which took up the entire Thursday morning. A small group of delegations from primarily capital-exporting states (Australia, Chile, China, the European Commission, Israel, Japan, Mauritius, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand and the United States) ultimately agreed on the core idea of the Swiss proposal. Strikingly, these states pertain either to the “incrementalist” or the “systemic” camp, with states advocating for more fundamental reforms being sidelined. When the chair announced the compromise in the plenary, the delegations of Morocco, Sierra Leone, Ecuador and the Democratic Republic Congo openly criticised the lack of transparency and participation in these consultations. In addition, a group of observing NGOs – SOMO, ITUC, Friends of the Earth Europe, ClientEarth and Public Citizen – made a joint intervention lamenting the further shrinking of the scope of the potential reform options as the notion of “structural reform” had now been equated with the creation of a multilateral investment court.

Furthermore, there seems to be a clear desire to intensify the work. The Working Group agreed(opens in new window) to request the Commission to consider allocating an additional week of conference time in 2019 to the Working Group in light of its anticipated workload. Moreover, various delegations suggested throughout the deliberations to set up smaller working groups, including intersessional meetings, expert groups and colloquia. This will undoubtedly lead to a fragmentation of the process, as not only delegations, particularly those from the Global South, but also observer organisations may face budgetary constraints, which will hamper the inclusive ambitions of the Working Group.

This content is available after accepting the cookies.

View on Twitter. Opens in a new windowPacked room during our side event at #UNCITRAL(opens in new window) to discuss the virtues and pitfalls of a Multilateral Investment Court #MIC(opens in new window) as possible option to reform #ISDS(opens in new window) . Many thanks to @haleybureau(opens in new window) @BrownColinM(opens in new window) @WallachLori(opens in new window) Prof Jane Kelsey and Prof Jaemin Lee for offering their lunch time pic.twitter.com/PGabYk9p9h(opens in new window)

— Bart-Jaap Verbeek (@BJVerbeek) April 4, 2019(opens in new window)

The way ahead

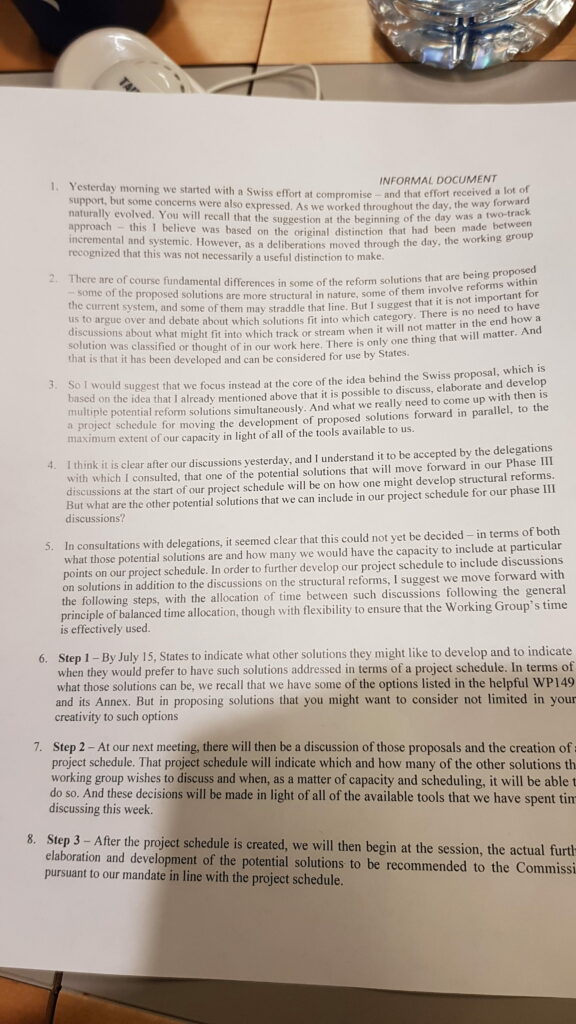

In the end, the Working Group agreed(opens in new window) to discuss and develop multiple potential reform solutions simultaneously, and that one of those solutions would be how to develop structural reforms. In order to further develop the project schedule to include other solutions, the Working Group agreed to move forward with the following steps:

- States can submit their preferred solutions to develop before 15 July 2019;

- These proposals would be discussed during the next session in Vienna, and the project schedule would be created, indicating which and how many of these other solutions the Working Group wished to discuss and when it would be able to do so.

- After the creation of the project schedule, the Working Group would begin the further elaboration and development of potential solutions at that session.

It is imperative that governments start thinking about their preferred solutions to meaningfully address their broader concerns with the ISDS regime (such as concerns related to regulatory chill, the asymmetric nature of ISDS, the undermining of third-party rights, and the circumventing of domestic legal systems). It was recalled that Working Paper 149(opens in new window) already contains an illustrative list of possible solutions, but these would only bring about either a mere tinkering or the institutionalization of ISDS. At the same time, governments should be wary about receiving recommendations from the Academic Forum(opens in new window) and the Practitioners Group(opens in new window) as many of their members are acting as arbitrator or counsel in ISDS cases and are therefore having a financial interest in the long-term survival of the system. The Working Group should remain open to input from diverse stakeholders and experts beyond these two groups.

Do you need more information?

-

Bart-Jaap Verbeek

Researcher